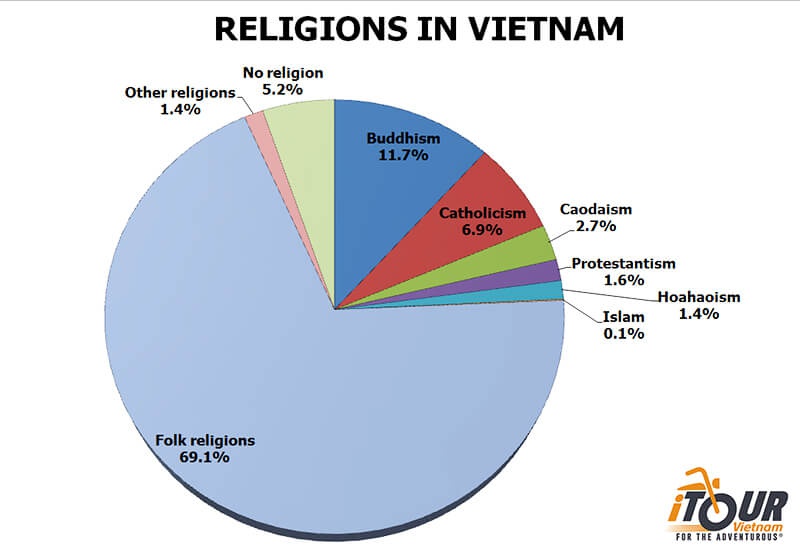

Question: Why is Vietnam so irreligious?

Answer: No, Vietnam is not irreligious and most of the people follow at least some kinds of the traditional beliefs or folk religious

(Sapa Pagoda in Vietnam)

The Religions in Vietnam

(Picture from the Hai Nguyen’s answer)

In this answer, we should help you understand more about the Folk religions in Vietnam.

A World of Gods and Spirits relating to the Folk religions.

One must begin with a sense of the richness and variety of traditional Vietnamese religion. Time was when the Vietnamese believed they inhabited a world alive with gods and spirits. Little distinction was made between the worlds of the living and the dead, between the human, the vegetable, the animal, and the mineral realms. If fate smiled upon one, nature, too, would be kind; but if one was cursed by fate, then even the elements would be hostile. The stones, the mountains, the trees, the streams, and the rivers, and even the very air were full of these deities, ghosts, and spirits. Some were benevolent, some were malicious; all had to be conciliated through ritual offerings and appropriate behavior.

So life was regulated by a vast array of beliefs and practices, taboos and injunctions, all designed to leash in these powers that held sway over human life. How much and in what way religion guided one's daily conduct depended on one's background. Confucian scholars, who prided themselves on their rationality, often scoffed at what they considered the superstitious nature of peasant religion. But they, too, were ruled by religious ideas. Different occupational groups had their own beliefs and practices. Fishermen, who pursued a much more hazardous livelihood than the peasants, were notorious for the variety and richness of their taboos. Some beliefs were shared by all Vietnamese. Others were adhered to only in one region or a small locality. Some were so deeply embedded in the culture as to be considered a part of tradition, holding sway over believers and non-believers alike.

If almost everything and everyone possessed a degree of power, so did the words employed to represent them. To a Vietnamese, saying a word out loud was to conjure up the object represented by that word, so that its presence and power became almost tangible. The more awe and fear a certain object inspired, the less often it was talked about, lest its power be called up. Elephants, tigers, crocodiles, and all the animals that threatened the lives of Vietnamese peasants were referred to in whispers, and respectfully called "lords." The personal names of emperors were avoided by all. The incidence of homonyms is quite high in the Vietnamese language, as it is monosyllabic. So in order to avoid using the imperial names to talk about the ordinary things of life, the names of the latter were often slightly distorted. For example, since the 17th century, when the country was divided into the northern territory under the Trinh lords, and the southern territory under the Nguyen lords, Southerners have used the word Huynh for "yellow," or "royal," in deference to Nguyen Hoang, the first of the Nguyen lords. For their part, northerners altered the pronunciation of tung into tong for "to submit" or "pine," to avoid pronouncing the name of their own ruler, Trinh Tung.

Ordinary Vietnamese went to great lengths to avoid naming their children after their relatives, dead or alive, for when a name was said out loud, all the people by that name were called up as well. It really would not do when scolding one's child, to be scolding Grandfather as well! The same awe of the power of names made parents call their children, not by their given name but by the order of their birth. But this was done differently in the north and the south.

Northerners were happy to have their first-borns be so known. But Southerners were more fearful of the devil, who coveted the children who were most cherished by their parents. It was thought that this would apply mostly to first-borns, and especially boys. So they pretended that their first-born was only their second child, and the ranking of children began with number two. Even in the 1960s, it was still possible to see small boys dressed as girls, nails painted and ears pierced, in order to fool the devil. This disguise would last until puberty, when parents would feel more confident that their beloved child would survive into adulthood, and when, presumably, it would no longer be possible to mislead the devil. The same reasoning made parents give their newborn babies truly hideous names, for the devil would not be jealous of such obviously unloved children. Then when adolescence was reached, a new and beautiful name would be chosen, to be recorded in the village rolls. Imagine the distress caused by the Western habit of entering permanent names at birth in birth certificates.

Religion governed life before birth, and well beyond the grave. Pregnant women were hemmed in by all sorts of taboos designed to protect them and their unborn child and to shield others from the power unleashed by this burgeoning life. Expectant mothers were told to eat certain kinds of food and to avoid others, to refrain from doing various things at night, or going to certain places. If, when pregnant, the mother ate crab meat, it was believed that the fetus would lie crosswise in her womb at the time of delivery. Eating oysters or snails would cause her child to drool. If she took part in a wedding or had herself photographed, her child would be charmless. Neither she nor her husband were to drive nails into their houses, or the birth of their child would be delayed indefinitely. Pregnant women were told to think happy thoughts, and, if possible, gaze at pictures of particularly good-looking children, so that their own child would be beautiful. On no account were they to give birth in someone else's home lest they pollute it beyond repair. They were not to cross fishermen's nets while these were being dyed, or they would bring them bad luck. The only way fishermen could counteract the curse put upon them by pregnant women would be to utter prayers that would cause the women to abort as soon as they reached home.

This is one of the very few instances of ill-wishing towards children. In general, the arrival of a child was cause for great rejoicing. When an infant reached its first full month of life, a great feast was held to give thanks. Another feast was held when the child was one year old. On that occasion, its parents would try to guess its future. Would the child, if a boy, grow to be a scholar, an artisan, a peasant, or a tradesman? That depended on which of the objects representing these four traditional occupations the child picked up when they were set before him. Then life was set, and no more birthdays would be held after that, until one had reached the ripe old age of 60, another time for rejoicing.

In death, one did not pass away. Instead, one passed on to another world, very close still to the land of the living. If one had led a good life, one could pass the merit one had thus accumulated on to one's descendants. Conversely, the progeny of a wicked person would suffer misfortune until all the evil had been expiated. The spirits of the dead could be called back by spirit-mediums, trance-masters, and other religious specialists to give advice to the living. If properly buried and worshipped, the dead would be happy to remain in their realm and act as benevolent spirits for their progeny. But those who died alone and neglected, and to whom no worship was given, disturbed the dead and preyed on the living. In order to appease these restless wandering souls, a grand feast was held on the full moon of the seventh month of the lunar year, the Feast of the Wandering Souls.

For one's ancestor to be particularly beneficial, he (for this applied mostly to male ancestors) must be buried in the correct spot. This necessitated the expertise of a geomancer. He would look at the lay of the land, the relationship between hills, and hollows and streams, and decide which would be the most propitious site. South Vietnam's most famous modern geomancer was known to carry out his field survey from the height of a helicopter, an example of how science and technology do not cause religious beliefs to dwindle away, but on the contrary, can serve to strengthen them.

Between birth and death, daily life was regulated by the determination of auspicious dates. Some inherently inauspicious ones were noted on the regular calendar and applied to all. For example, no one would dream of doing anything of importance on the 5th, the 14th, or the 23rd of the lunar month. If one did think of embarking on a new venture, be it building a house, embarking on a journey, or starting a new business, then it would not be enough to avoid these unlucky dates; a truly auspicious one must be sought. This would require a fortuneteller, who could be an astrologer, a horoscope caster, an I-ching diviner, a palm-reader, or some other expert in the art of reading the future and divining the wishes of the gods. There was a general in the South Vietnamese army who was notorious for refusing to venture out of his headquarters without first consulting his soothsayer, no matter the orders from above or the strategic needs of the moment.

The above sketches of the day-to-day manifestations of traditional religious beliefs only hint at the richness and variety of Vietnamese religion. But these images help serve as a backdrop to the larger question of the role of religion in Vietnamese society and politics. My underlying theme is that both religion and politics are about power, conceived differently to be sure. This shared concern for power has been both a bond and an enduring source of tension between the two throughout Vietnamese history.

The Gods of the Early Vietnamese

Vietnamese religion was a syncretic amalgamation of the three great religions of East Asia—Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism—onto which had been added a rich variety of preexisting animist beliefs. All Vietnamese believed in this single religious conflation in one form or another, but these forms varied greatly. Scholar-officials gave more weight to Confucian teachings; common people put more emphasis on Buddhism and on Taoism in its popular religious form.

In all probability, the religion of the early Vietnamese before the Chinese conquest was totemic. Birds feature heavily in the decoration of the famous Dong Son bronze drums fabricated between the third and the first century B.C. This has led historians to assume that birds were important objects of worship. The early Vietnamese believed that they were descended from a dragon-king who had mated with an immortal from the mountains to produce 100 children. Hence, the recurring dragon motif in Vietnamese decorative art. They also believed that as a people, they enjoyed the protection of the turtle god who appeared at times of national crisis to give the leader of the day the weapons with which to fight off his enemies. The last appearance of this turtle god was in the 15th century when Le Loi, the leader of a guerrilla mo