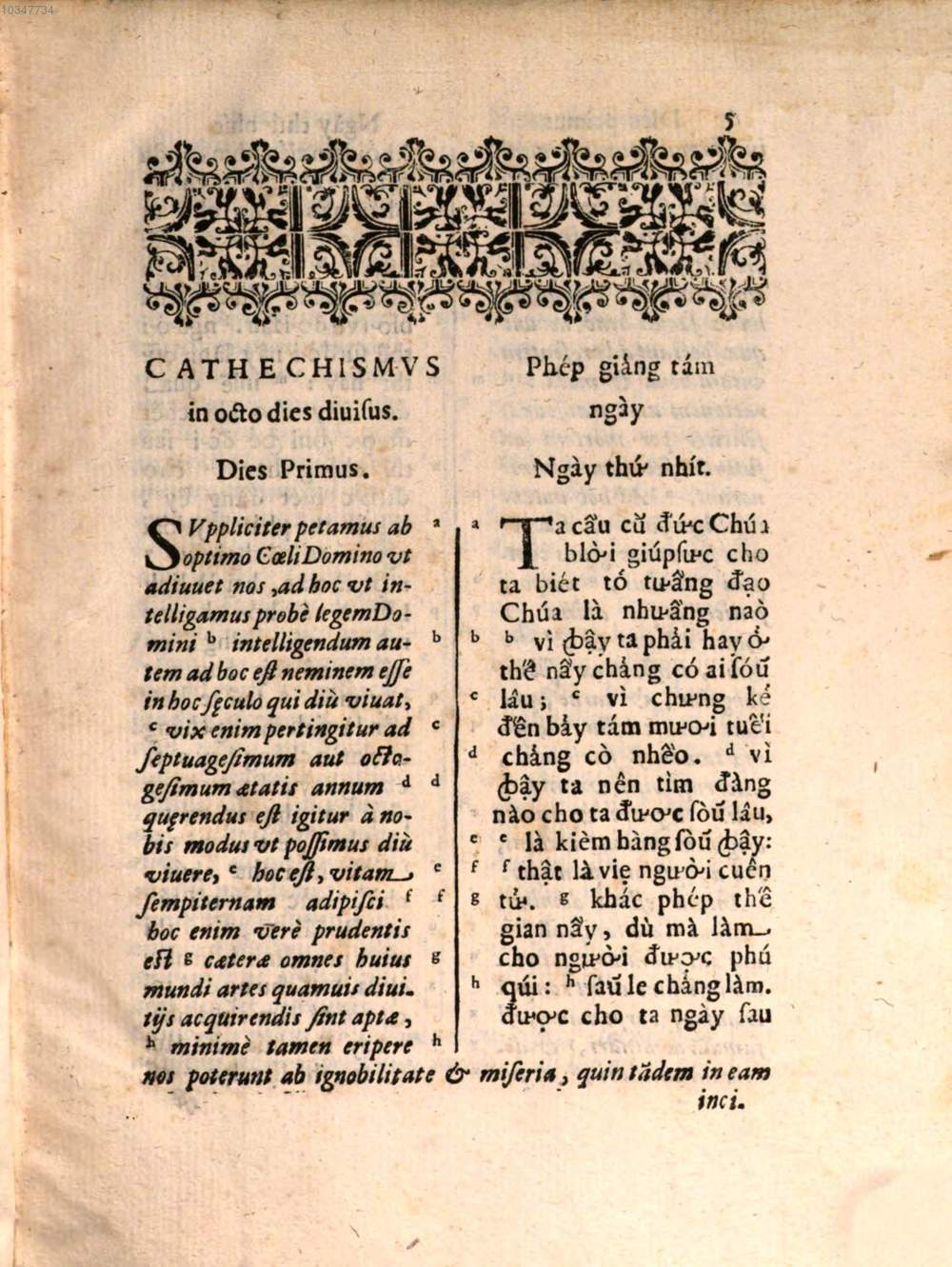

Very interesting question. Let’s turn back to a very famous document 370 years ago, the “ Cathechismus for eight days ” published in 1651 by the commissioner Alexandre de Rhodes. Here is one page of that book.

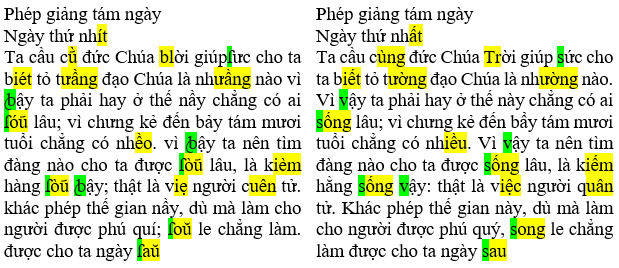

I’ve just highlighted some differences between the old text of Middle Vietnamese to the left and the modern day equivalence in the right, in which consonants are green and vowels are yellow.

It is very interesting that almost all spelling and tonal diacritics have been reserved exactly as modern day. Leaving apart the lexicon and syntax, some differences in pronunciation and spelling are still understandable and comparable with modern standard such as: ưâng = ương ; iet = iêt ; êo = iêu , etc. Some spelling look weird like “u᷄” for “ung”, “ou᷄” for “ông” and “au᷄” for “ong”. That might be due to the Portuguese spelling of nasal vowels back then, but not a huge difference. The most significant is the consonant “ ꞗ ” (b with flourish, supposed to be pronounced like “w”) and the consonant cluster “ bl ” that had never been used anymore.

Now, I make a test with a very simple sentence, using Middle Vietnamese pronunciation: “ Blời ơi, chỉ có wậy à? ”

It look actually weird but still is understandable after thinking a while.

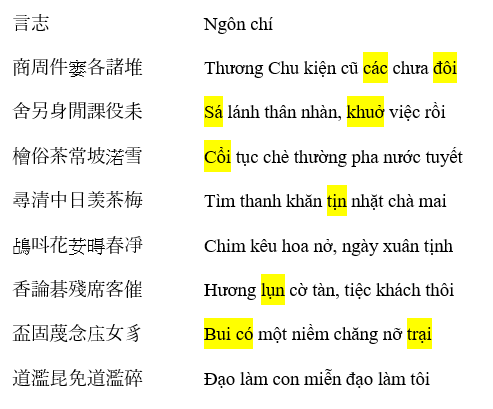

OK, let’s go farther to c.a. 1400s with a poem in the National language poetry collection (Quốc âm thi tập 國音詩集) of Nguyễn Trãi written in Nôm script. Nôm is to the left and modern translation is to the right.

I have also highlighted the unintelligible words to modern Vietnamese. Regardless to the pronunciation since we don’t know how the pronunciation was back then, the context was also difficult to understand without translation and/or explanation.

I do again the above test with changing on word: “ Blời ơi, bui có wậy à? ”. If heard someone asking that, I would definitely think: “WHAT, WHAT’S THE LANGUAGE?” because it is totally unintelligible.

The sentence is just simple: “Trời ơi, chỉ có vậy à?”

Conclusion, languages seem to have evolved the same linear regardless whomever the languages spoken by. An English speaker is hard to understand English spoken in Shakespeare’s era. In a similar manner, Vietnamese cannot understand Vietnamese spoken in Nguyễn Trãi’s era aka 600 years ago.

Hope it helps.